Life Through the Lens: Quynh Vu

Vu, an artist, grapples with expectations of the art made by women of color.

“Through my work, I will attempt to sacralize dry cleaning objects and address the invisibility of blue-collared labor,” Vu said

February 17, 2022

As a visual artist and person of color, I often joke about the stereotype that is BIPOC artists who only create heavily politicized art that depicts an angry, anti-West attitude. That stereotype depicts ours as the kind of radical, ultra-leftist art that criminalizes whiteness and victimizes the BIPOC identity by hitting on certain themes such as imperialism, westernization, colonization and more.

I believe that I can safely say that many artists of color face the fear of being categorized as this kind of artist. Unfortunately, BIPOC artists are given the involuntary responsibility of representation. To exist as an artist of color in a Western-centric art world, there is an implicit obligation to create politicized work about identity in order to be legitimized and noticed. Our work, no matter what it is, often becomes diminished to a representation of our identity that is superficially interpreted based on white experiences and white logic. Our attempts to present ourselves as complex individuals are thus prohibited by this reductive logic.

The 2008 book “White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology” is a collection of essays that address white logic — specifically in the fields of social science. The essays elaborate on how social scientists’ adherence to white common-sense influences how certain data and issues are studied, framed and analyzed. As a result, the research presented comes from a restricted understanding of the true complexities of racial matters. The book calls for a total overhaul of current social research practices and more of an effort towards a more multicultural approach.

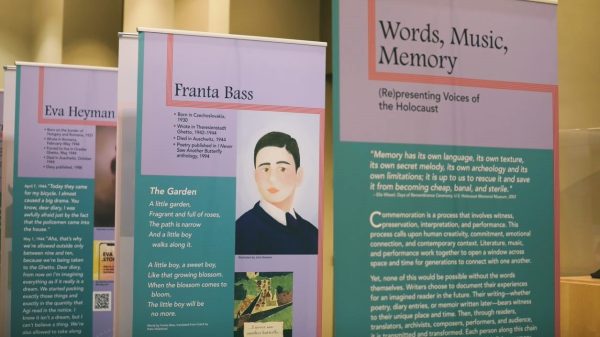

Though this book speaks for practices within social sciences only, it is heavily applicable to the art world as well. Art history is organized from a Western-centric perspective. Total self-expression through abstract painting was invented in the United States by Jackson Pollock. Black artists are ambassadors for the Civil Rights Movement. Aboriginal artists physically manifest the height of spirituality onto the canvas. Whiteness has always been the dominant culture and art will continue to be interpreted by its limited perspective.

The New York-based artist, Jayson Musson, addresses this issue in a satirical comedic video he filmed entitled “How To Be a Successful Black Artist”. In this nearly 9-minute-long video, he embodies his fictional persona, Hennessy Youngman and gives his Black audience a list of actions they could take in order to be successful in the art world. In the video, he lists things such as building and maintaining an angry exterior by watching violent footage of racist acts, exotifying/othering yourself, inventing pseudo-scholarly terms such as “post-Black” and relying on slavery for content.

If I want to escape this fear of categorization so badly, then why do I keep focusing on diasporic content? There is a reason why so many artists continue to create work that consequently lands them in this category. Being a person of color in the West is too complex not to talk about. It is a kind of existence that naturally produces confusing and exhausting questions about identity. It is not a means of dwelling on the negatives of the past but an attempt to understand how and why my identity is largely shaped by the consequences of both historical and contemporary globalism.

I often say that this is the type of content that “white people eat up.” Their exposure to this type of work is a means for them to soothe their white guilt and prove their wokeness. It’s the kind of work that sells.

I usually feel guilty when I create a work that is not political. It feels almost shameful when I create a piece where the goal is solely to explore mark-making or the nature of a particular medium. If I cannot justify a work using politics and theory, then it is not worth creating or displaying. At the same time, I feel proud when a work has nothing to do with politics of identity, saying to myself, “Hey, I can be like white people too.” Ironically, creating unpolitical work about nothing at all feels like a rebellion against dominant white culture. Simultaneously, I again feel guilty when creating work that does tackle these issues of identity. It results in feeling like a sell-out and that my work is too predictable. It creates a crisis of self-fetishization and self-exploitation.

We must stop relying on these white perceptions to be the default of how our art and ourselves will be received.

All of these feelings are a result of letting white opinions determine validity. Our identities as BIPOC in the West are complex, but it is a matter of trying to convince white people of that.

I was asked by one of the Life editors in an email to write an article about my work. In the email, the first article for “Life Through the Lens” was linked. Admittedly, I was disappointed to discover that this particular article dealt with the frustrations of being a person of color in a predominately white environment. This topic was consistently reflected upon throughout other articles for the column. I felt that the opportunity to write this article was yet another way that I have been viewed as an angry representative of the Asian American identity.

While writing this article, I was confused about who I was writing for. I am not much of a writer; hence why I make images. So, I attempted to answer my question by understanding who I make art for. The large majority of my work does critically investigate the Vietnamese-American diaspora by reckoning with transnationalism, the residual effects of French imperialism, and the general existence of Asian-Americans in the West. Investigating these topics helps to provide insight into my diasporic experiences. It works as an attempt to form a concrete idea of who Quynh Vu is. My work is specific to my individual self only. If I am representing a particular group of people, then that is an unintentional side effect.

It felt almost redundant to write about my work as if my work is something that I make primarily for myself. Maybe this is just an elaborate journal entry full of organized venting. However, I am considering the possibility that it may serve as a statement defending my work for white people or even for the editor himself.

Truthfully, every artist’s work pertains to their identity. As people, everything we do is a symbol of our identity. How we choose to dress, eat, walk and wipe our butt. But as people of color, our bodies are already so politicized that everything we create and do automatically has preconceived meanings shaped by white logic. So, we must stop relying on these white perceptions to be the default of how our art and ourselves will be received.

For my upcoming solo show in the spring of 2022, I will focus on the two largest components of my childhood, which are dry-cleaning and Catholicism. I spent nearly every day of my childhood alongside my parents in their dry-cleaning business. The only day that I wasn’t there was on Sundays when the business closed, and we went as a family to attend mass at the nearby Roman Catholic church. Through my work, I will attempt to sacralize dry cleaning objects and address the invisibility of blue-collared labor.